Wonder: vertical integration for mealtime, not “another delivery app”

Hey—

I want to test a simple question. Can a vertically integrated operator in food delivery actually earn its keep when the default market structure rewards asset-light marketplaces that skim take rates and shove the hard problems back onto restaurants and couriers. That question sits at the center of Wonder, Marc Lore’s bet that a “mealtime super app” will beat marketplace gravity by owning more of the stack: brands, kitchens, logistics, data, and the front end that customers actually touch. Fast Company called it a mealtime super app earlier this year. The label is noisy, but the direction is right.

If you strip away the marketing and look at the operating facts, you get a cleaner picture. Wonder is now a portfolio of three big things. It runs multi-brand food halls with its own licensed concepts and chef IP. It owns Blue Apron, so it reaches into meal kits and retail. And since January 2025 it owns Grubhub, which gives it a national marketplace, delivery fleet density, and access to a very large demand pool. That is a different beast than a pure delivery marketplace.

Below is the case as it stands today, with real numbers, and then the operator questions that matter if you are evaluating this as strategy rather than story.

What changed since the early vans

The first Wonder version used vans to finish food at the curb outside your house. That idea got press attention and neighborhood pushback. It also had obvious scaling and cost issues. By early 2023 the company pivoted to ventless finishing kitchens inside fixed sites and food halls. Think commissary prep upstream, rapid-cook equipment downstream, and a format that can go into smaller boxes, including inside big box retail.

Two follow-through moves made that pivot real. In September 2023 Wonder agreed to acquire Blue Apron for about 103 million dollars, which closed in Q4 2023. That planted a flag in at-home meal occasions beyond hot delivery. Then in November 2024 Wonder agreed to acquire Grubhub from Just Eat Takeaway for about 650 million dollars, and the transaction closed on January 7, 2025. Now the company sits across dine-out delivery, takeout, and make-at-home.

On top of M&A, Wonder raised serious growth capital. After a 700 million round in 2024, Wonder announced another 600 million in May 2025, tied to a plan to nearly double sites this year. Trade press pegs the valuation north of 7 billion and suggests a run rate of 90 units by year end 2025. Business Insider counted 56 open locations as of early August and the company said 90 by year end. That is the stated trajectory.

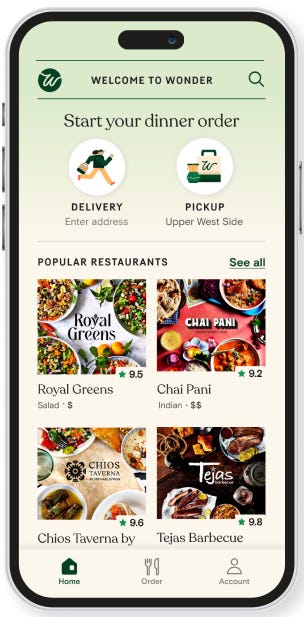

The front-end experience also changed. The consumer app lets you order from multiple partner brands in a single check and single delivery. That is not novel in airports or food halls, but at neighborhood scale with owned kitchens it lets Wonder optimize ticket size and route clustering in ways marketplaces cannot.

The integrated stack: why own more than the app

Here is the underlying logic:

Acquisition and frequency: Grubhub’s marketplace footprint lowers CAC for the Wonder portfolio and raises order density on the last mile. You redirect marketplace demand into higher margin, controlled SKUs when you can. The sale completion is cleared and public.

Assortment control: Chef IP and in-house concepts give Wonder exclusive menus and engineered items designed for delivery constraints. HNGRY reports Wonder has spent tens of millions acquiring rights to chef concepts and uses ventless, TurboChef-style finishing to standardize quality and site selection. In plain English, you choose the menu for the medium, not the other way around.

Upstream flexibility: Blue Apron adds a kit and retail layer. That means the same upstream commissary and vendor relationships can serve hot, chilled, or kit formats. Volume and SKU planning can flex with daypart and seasonality. The Blue Apron deal terms are on the SEC site and wire coverage.

Throughput and basket: Multi-brand single-order checkout increases AOV and lets you load balance kitchens. Wonder markets cross-brand ordering explicitly. That feeds routing, batching, and quote times.

Unit growth: The company is saying 90 locations by the end of 2025. Press coverage ties that to the 2025 raise. If they actually open on that cadence, their delivery footprint fills in on the East Coast first.

Viewed as a system, the thesis is simple. Move from a thin marketplace take rate to a fatter integrated margin by owning more of the value chain and keeping the consumer in your own loop. That only works if the operational complexity does not crush you.

What “mealtime super app” must mean in practice

I do not care about the label. I care about the mechanics behind it.

Menu engineering for the medium: Short cook cycles, low variance, ingredients that hold heat and texture in a box. If you build a menu for dine-in and ship it, your refunds tell the story. This is where chef IP matters only if it is translated into delivery constraints. HNGRY’s reporting on ventless finishing, exclusive licensing, and commissary strategy is consistent with that outlook.

Order orchestration: One order can hit multiple micro-kitchens. You need a kitchen display system that splits the ticket and a delivery system that reassembles at the handoff. Wonder advertises multi-brand single-order delivery to consumers. That implies routing and sequencing logic under the hood.

Network effects that are not fake: Grubhub gives density. Density improves on-time percentages and driver utilization. When your own brands are in the mix, you can bias the system to your highest contribution margin SKUs without violating marketplace fairness because you own the marketplace. The sale completion is public. Fast Company’s “super app” tag reflects this integration narrative even if the term is loose.

Occasion expansion: Blue Apron turns the same customer into a kit or retail buyer. The company now has a credible reason to message weeknight dinners, weekend kits, and ready-to-eat all from one identity. SEC filings confirm the deal.

If the stack works, you win on frequency and cross-sell, not just on speed.

Where execution gets hard

The weak points are always in the plumbing.

Kitchen complexity: Multi-brand lines create entropy. Ticket splitting, POS consolidation, and expo timing break when volume spikes. HNGRY lays out the pain points for multi-brand halls and notes that not every competitor made the model work. Wonder counters with commissary prep and ventless finishing. That reduces skill variance but pushes more load into upstream planning.

Commissary economics: Central prep increases yield and QA. It also concentrates risk. If a central node misses a prep window you cannot fix it at the edge. Data on Wonder selling commissaries to a manufacturer is reported in HNGRY’s piece as context on the supply puzzle. The principle stands either way: upstream reliability is life or death when you finish at the edge.

Marketplace integration: Grubhub brings volume but also legacy constraints. You have to integrate courier pools, SLAs, fraud systems, and partner obligations without breaking contribution margins in your own halls. The sale is done. The integration cost is unknown outside the company.

Labor model: You reduce culinary variance with semi-automated finishing, which lets you hire for reliability rather than high chef skill. That helps margins, but you still need line balance and training. Business Insider’s recent field test suggests Wonder is getting speed right in many locations, with room to tighten ordering UX. That sounds like the typical early scaling mix.

Local regulation and boxes: Ventless equipment widens the map of viable sites and speeds permitting. It also means you are betting on specific equipment vendors and uptime. If a bank of ovens is down on a Friday, your promise dies at the worst possible time. HNGRY calls out the ventless approach as a strategic enabler.

Competitive set and why the model is not the same as DoorDash

DoorDash, Uber Eats, and Grubhub built liquidity moats that look like classic two-sided marketplaces. They do not want OPX complexity. They want to match, not make. That is why their gross margins act like software and their net margins look like logistics. Wonder is choosing the opposite. Make more, match some, and own the experience. The Fast Company profile captured that framing. The Eater explainer shows how we got here from vans.

The obvious advantage you trade for complexity is product control. If you can deliver predictable quality at a fair price with exclusive menus and shorter quote times due to route clustering, you can build a brand that is not interchangeable on a marketplace carousel. That is the bet.

What to watch

I would track operating signals that predict margin.

On-time and complete across multi-brand tickets: If the single-basket promise is real, on-time percentages for multi-station orders should converge toward single-station orders within a few months of a new site opening. The consumer site advertises the feature. The proof is service reliability at dinner rush.

Attachment and AOV growth: Cross-brand add-ons should lift average order value over the first 90 days of a cohort if the UX and expo flow are right. If not, the multi-brand promise is not moving behavior.

Prep upstream, waste downstream: Commissary driven systems live or die on yield. If waste climbs with volume, finishing at the edge cannot save you.

Blue Apron conversion and retention: If Wonder can convert delivery users into kit buyers without excessive promo spend, you see a real multi-occasion flywheel. The SEC exhibit and wire coverage confirm ownership. The funnel is the unknown.

Post-close Grubhub mix: If marketplace demand feeds Wonder’s owned SKUs without cannibalizing partner restaurants in a way that triggers backlash, that validates a delicate balance. The sale close is public. The partner reaction is what to watch.

Store cadence against guidance: May guidance and local press suggest a store-a-week pace tied to the 600 million raise. The Insider piece lists current count and year-end target. If the cadence slips, you reassess the capital plan.

Where AI actually fits, beyond the slogan

Kitchen forecasting: Predict SKUs at the commissary by weather, local events, and historical mix by hour so the finishing line never starves.

Order clustering: Use marketplace density to route multi-brand baskets with minimal deadhead. You now control both assortment and routing. That is rare.

Menu feedback loop: Tie refunds, low star ratings, and reheat times to recipe iteration. Kill SKUs that do not travel.

Personalization: If someone orders a spicy protein bowl and kids mac and cheese on weeknights, you know what to suggest on Friday. The front-end site is already set up for multi-brand carts. That is the hook.

None of this needs a hype label. It needs clean data across commissary, kitchen screens, courier apps, and the consumer app. If the data model is messy, the promise breaks.

Here is the simplest statement I can make after reading the filings and the trade coverage. Wonder is not a marketplace with a new skin. It is a vertically integrated food platform that just bought one of the three major US marketplaces and already owns a national meal kit brand. It is spending heavily to scale owned locations and is explicit about letting customers bundle multiple brands in one delivery. Those are objective facts.

If they make the plumbing work at scale, they get frequency, higher AOV, and routing advantages that thin marketplaces cannot match. If the plumbing buckles, they carry costs that marketplaces never had to carry. That is the trade.

If they move the right way by Q4 and Q1, the system is working. If they do not, the model is still a work in progress.